Every time you browse a website, you’re using HTTP under the hood. HTTP is an underlying protocol used by websites that allows sending and receiving webpages; it’s also the foundation of the modern Web.

Understanding how HTTP works under the hood is useful, because it helps you at troubleshooting, optimizing, and securing websites.

The basics

HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) is a protocol used by websites. It allows sending and receiving webpages, and transferring files.

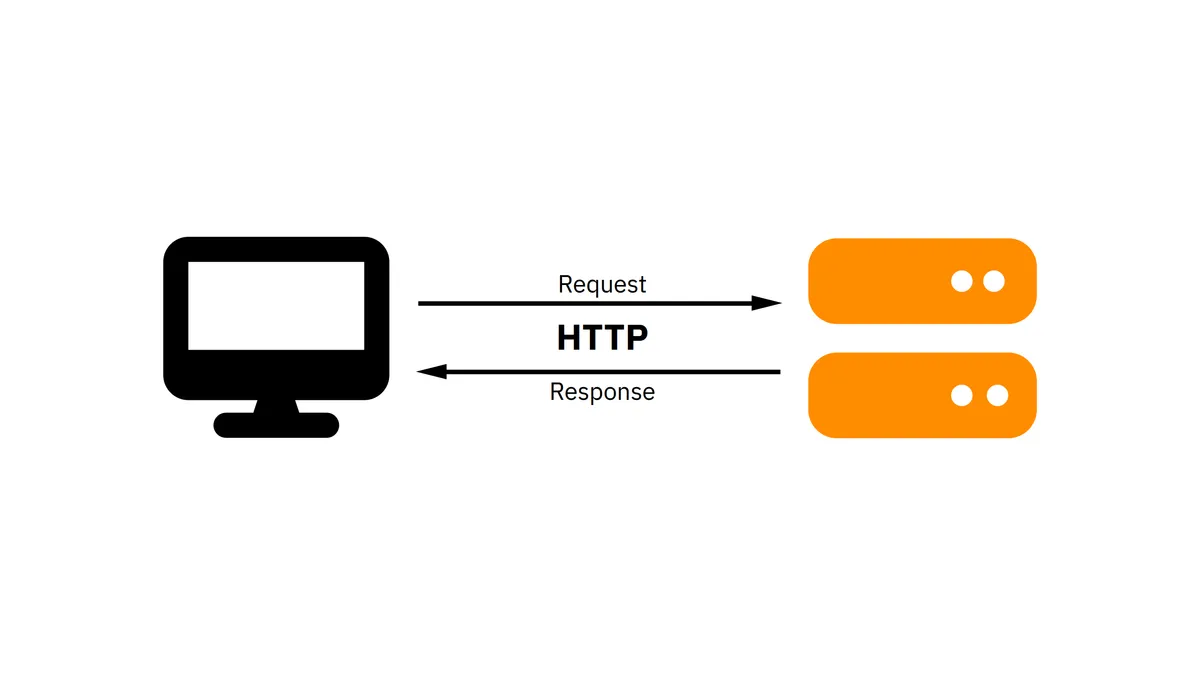

HTTP uses a request-response model, that means that the web client (often a web browser) sends a request first, and after the web server reads the request, it sends a response.

HTTP is also stateless; this means that with the HTTP protocol itself, the server doesn’t retain state from previous requests.

The HTTP protocol had some significant changes since it was first introduced.

HTTP/0.9, introduced in 1991, allowed for simple file transfers and basic web browsing, but it didn’t support uploads.

HTTP/1.0, introduced in 1996, introduced the concept of HTTP requests and responses, basic error handling, and allowed uploads.

HTTP/1.1, introduced in 1997, improved by HTTP/1.0 by introducing presistent connections, which allows multiple requests to be sent over a single connection; this improves the website performance, because it might take some time to open a connection.

HTTP/2, introduced in 2015, introduced multiplexing, which allows many requests to be sent over a single connection simultaneously; this improves the website performance even more.

And the latest HTTP version - HTTP/3 - introduced in 2022, uses QUIC (a transport layer protocol built on top of UDP) instead of TCP; this can improve the website performance even more than the previous HTTP version.

What happens when you enter a URL in the browser?

When you enter a URL in the browser, first the web browser needs to know what server to connect to. The domain name (for example www.ferronweb.org) is extracted from the URL (for example https://www.ferronweb.org/), and it then gets translated to an IP address (for example 194.110.4.248) through DNS. An IP address identifies a server the web browser will connect to.

Next, the web browser establishes a TCP (or QUIC, if using HTTP/3) connection with the server. After establishing the connection, if the URL is an HTTPS one, it performs a TLS handshake to set up data encryption between the web browser and the web server.

After the connection is established, the web browser sends an HTTP request containing data, such as the resource path (like /), the HTTP method (often GET) and headers.

After the web server sends the request, the web server responds with an HTTP response, which contains the status code (such as 200, meaning a successful response), headers, and the response body (which contains the data from which a webpage is rendered).

After receiving the response, the web browser renders the webpage from the received data. The web browser can also ask the web server for additional resources (such as images, stylesheets, scripts), making additional requests.

Inside the HTTP request

Inside the HTTP request, there are several elements.

Here’s an example HTTP request (for HTTP/1.x):

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

The lines in the HTTP/1.x requests end with two control characters - carriage return (CR) and line feed (LF).

In the request, the HTTP method (for example GET), the request path (for example /), and the HTTP version (for example HTTP/1.1) are specified. The HTTP method describes what action will be taken, and the request path specifies where it will be taken.

There are also headers in a HTTP request, for example Host (which specifies the server hostname, often a domain name) or User-Agent (which specifies what HTTP client was used).

Optionally, for POST and PUT methods, there is also a body containing data to be sent to the server.

Inside the HTTP response

Inside the HTTP response, there are also several elements.

Here’s an example HTTP response (for HTTP/1.x):

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/plain

Content-Length: 12

Hello World!The lines in the HTTP/1.x responses end with two control characters - carriage return (CR) and line feed (LF).

In the response, the HTTP version (such as HTTP/1.1), the status code (such as 200), and the status code description (present in at least HTTP/1.x, for example “OK”) are specified. The status code describes the state of the HTTP response.

The list of some HTTP response status codes is as follows:

- 200 OK - the request succeeded

- 201 Created - the request succeeded, and a new resource was created

- 301 Moved Permanently - the resource was moved permanently to another location

- 302 Found - the resource was moved temporarily to another location

- 400 Bad Request - the request is invalid

- 401 Not Authorized - authorization is required to access the resource

- 403 Forbidden - the access to the resource is denied

- 404 Not Found - the resource wasn’t found

- 405 Method Not Allowed - the server doesn’t allow the method used to access the resource

- 429 Too Many Requests - there were too many requests send to the server

- 500 Internal Server Error - the server has encountered an unexpected error

- 502 Bad Gateway - the server received an invalid response when acting as a proxy

- 503 Service Unavailable - the service provided by the server isn’t available

There are also headers in a HTTP response (like in a HTTP request), for example Content-Type (which specifies the type of the response body, like text/plain for plaintext) or Content-Length (which specifies the length of the response body).

For many HTTP responses, there is also a body containing data received by the client.

HTTP headers: more than metadata

HTTP headers aren’t just metadata for the requests and responses, they can also specify caching, content negotation, authentication, and compression.

Some request headers are as follows:

- Accept - specifies the format of the response data (like

text/plainfor plaintext) - Authorization - provides credentials for authentication (like

Bearer <token>) - Content-Type - specifies the format of the request body (like

application/jsonfor JSON data) - Host - specifies the server hostname (often a domain name)

- User-Agent - identifies what client made the request (like

curl/8.5.0)

There are some of the response headers, which are as follows:

- Content-Length - specifies the response body size in bytes

- Content-Type - specifies the format for the response body (like

text/htmlfor HTML data) - Location - specifies the URL to redirect to

- Set-Cookie - specifies a cookie to be set on client’s browser

- Server - identifies the server software (like

Ferron)

Connection management

In HTTP/1.1, TCP connections can be reused (this is also called “keep-alive”). This can be enabled by sending a Connection: keep-alive header to the server when making a request. TCP connection reuse can improve the website performance, as it might take some time to establish a TCP connection.

In HTTP/2, requests are multiplexed, that means that many requests can be sent to the server at once. This can improve the website performance even more.

In HTTP/3, the QUIC transport-layer protocol (which uses UDP under the hood) is used instead of TCP. This can improve the website performance even more, as in TCP a single lost packet can delay all subsequent packets (this can be also called “head-of-line blocking”).

Cookies and sessions

Cookies are set by sending Set-Cookie headers from a web server. A Set-Cookie header contains a cookie name, a cookie value, and cookie flags.

A Set-Cookie header can look like this: Set-Cookie: session_id=1234567890abcdef; Expires=Wed, 21 Oct 2025 07:28:00 GMT; Domain=example.com; Path=/. This example specifies a session_id cookie set to 1234567890abcdef, with a specified expiry time, for the example.com domain and its subdomains and for paths containing / at the beginning.

The web browser will then receive and store the cookie in its storage.

When making a request, the web browser retrieves cookies from its storage, and sends cookies through the Cookie header to the server, which can look like this: Cookie: session_id=1234567890abcdef. This example specifies a session_id cookie set to 1234567890abcdef.

Cookies can be used for maintaining state (for example authentication or tracking)

There can be some security concerns, when it comes to cookies though. It’s recommended to set a SameSite flag, which specifies whether to send cookies across domains. Also, there are HttpOnly attribute, which disallows access through client-side scripts, and Secure attribute, which allows sending cookies to the server only with encryption (HTTPS).

HTTPS and TLS

HTTPS extends HTTP protocol by adding encryption. The encryption is done through TLS (Transport Layer Security), or in earlier days, SSL (Secure Sockets Layer).

When the web client connects to the web server through HTTPS, the TLS handshake is done.

First, the client sends a message to the server (“Client Hello”) containing the TLS version, a random number, and the list of supported cipher suites.

Then the server responds with another message (“Server Hello”), containig the TLS version, a random number, and a chosen cipher suite.

Then the server sends the digital certificate (a TLS certificate), which contains its public key and identity information.

The client then verifies the certificate by checking if it’s valid, ensuring it was issued by a trusted certificate authority (CA), and if it matches the expected identity information.

After the verification, the client and the server perform a key exchange using the chosen cipher suite, for example using Diffie-Hellman (DH) or Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH) algorithms.

Later on, the client and the server send a “change cipher spec” message that indicated that they’re switching to the newly established keys.

Finally, both the client and the server send a message confirming that the handshake is complete.

Encryption provided by TLS is important, because it ensures the integrity of data, and protectes data from eavesdropping. TLS certificates are also important, because of chain of trust; reputable certificate authorities shouldn’t issue a certificate for a domain name to someone, whom the domain name doesn’t belong to.

Inspecting HTTP

There are many ways to inspect data to learn how HTTP protocol works, such as using web browser’s developer tools, or using curl to make HTTP requests.

To make a basic HTTP request with protocol information shown using curl, you can run this command:

# Replace "https://example.com" with the desired URL.

curl -v https://example.comThe -v flag indicates verbose output (that includes HTTP protocol data).

The example output (for curl -v http://www.ferronweb.org command), can look like this:

* Host www.ferronweb.org:80 was resolved.

* IPv6: (none)

* IPv4: 194.110.4.248

* Trying 194.110.4.248:80...

* Connected to www.ferronweb.org (194.110.4.248) port 80

> GET / HTTP/1.1

> Host: www.ferronweb.org

> User-Agent: curl/8.5.0

> Accept: */*

>

< HTTP/1.1 301 Moved Permanently

< location: https://www.ferronweb.org/

< content-security-policy: default-src 'self'; style-src 'self' 'unsafe-inline'; object-src 'none'; img-src 'self' data:; script-src 'self' 'unsafe-inline' 'unsafe-eval' https://analytics.ferronweb.org; connect-src 'self' https://analytics.ferronweb.org

< x-content-type-options: nosniff

< x-frame-options: deny

< strict-transport-security: max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains; preload

< cache-control: public, max-age=900

< server: Ferron

< content-length: 0

< date: Mon, 14 Jul 2025 19:45:09 GMT

<

* Connection #0 to host www.ferronweb.org left intactIn this example, the domain name gets resolved, the client is connected with the server, the client send a request, and gets a response with 301 status code, implying a permanent redirect. The redirect is to https://www.ferronweb.org/, as indicated by the Location header.

Conclusion

Understanding how HTTP works under the hood gives you deeper understanding of how the web functions, from the moment you enter a URL to the final rendering of a webpage. It helps you troubleshoot connectivity issues, optimize performance through connection reuse and protocol choices, and ensure better security with HTTPS, headers, and cookies.

As web technologies continue to evolve, with newer versions like HTTP/3 and underlying protocols like QUIC, grasping the core principles of HTTP remains as important as ever for developers, network engineers, and anyone interested in how the internet truly operates.